I have a lot to say.

Today we released a new episode of 1-800-1800 that is unlike any of the nine episodes that have come before. Instead of talking about one single year of the long nineteenth century (what we define as sometime between 1776 and 1919), we talk about a work of popular culture, from the twenty-first century, no less!

This episode was inspired by two recent and utterly charming encounters with our growing Mandylion public. Back in April, we had the pleasure of joining the “Unusual Appetites” book club at McNally Jackson. Hosted by Quinn and Melanie, this group of charmers gathered to read One or Two. We reveled in the club’s insightful feedback, including their insistence that we go home immediately and watch The Substance, a 2024 film starring Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley with some major thematic resonances with H.D. Everett’s 1907 masterpiece. And last week, we tabled at the Paris Ass Book Fair, where for three straight days we talked to hundreds of people about our project. We repeated the plots of our books so many times that they started playing on a loop in my brain. Time and time again, when we told our new friends that One or Two is about a woman who goes to a séance to lose weight, only for her lost weight to materialize as her younger self, people responded by saying, “Oh, so like The Substance?” (Sometimes they said it in French, oui.)

It turns out that watching The Substance is a lot harder than telling people you’re going to watch The Substance. Madeline was so revolted that she watched the film mostly through her t-shirt. See exhibit A. Listen to the episode to hear our hottest takes on this most lukewarm of films.

I took a break from editing the episode to go to the opera. I am by no means an opera buff, but I always enjoy a visit to “the other Met,” as I like to call it. In recent years, I’ve seen Don Giovanni with my mother, La bohème with my besties, and The Magic Flute with my beloved. Though I was suffering an attack of P.J. Clarke’s-induced food poisoning during this latest visit, it was still my most transporting opera experience ever because I saw Salome. I have decided that this is not only my favorite opera but the best opera ever written.

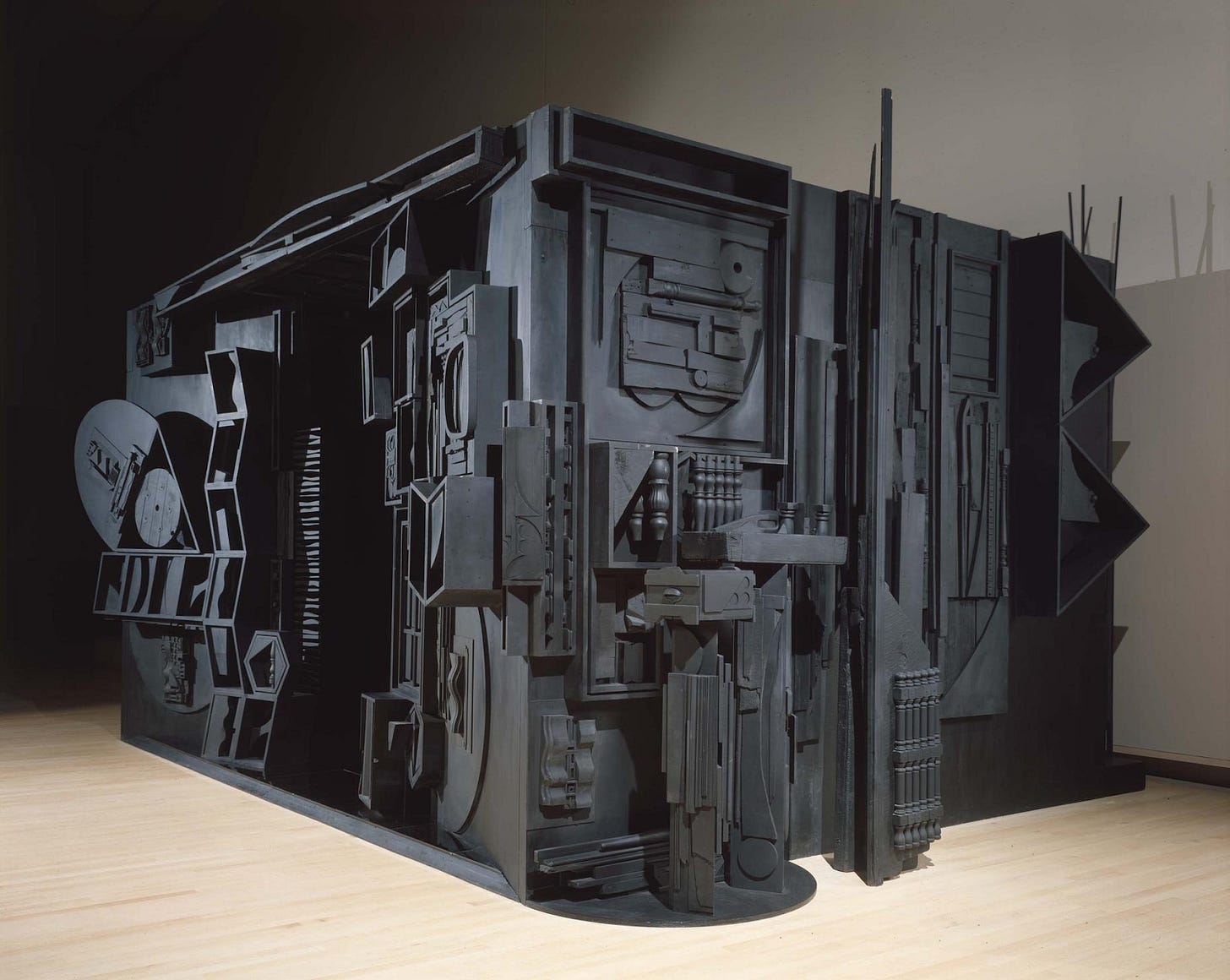

German composer Richard Strauss based the opera on Oscar Wilde’s scandalous 1891 play, which was in turn based on the New Testament story of John the Baptist’s decapitation, ordered by King Herod’s stepdaughter Salome. This new production at the Met was directed by Claus Guth. I’ve learned that most productions of Salome are staged in biblical times. But Guth set his rendition in a haunted Victorian mansion with black walls that reminded me of Louise Nevelson’s sculpture Mrs. N’s Palace (1964-77).

Against this solemn backdrop, we meet Salome. Unlike in previous productions, she’s not dolled up in a beaded bikini—which I guess is supposed to be what princesses wore B.C.? Instead she’s wearing a black velvet dress with a lace collar that reminds me of a Batsheva dress I bought to wear to an ultraorthodox Jewish wedding that I returned because it was giving “your culture is my costume.” See exhibit B. (I wore my handy Dior skirt suit instead. I’d include a photo but I think I might wear it to our EVENT next week at Grolier Club! We are so excited about this. It’s on June 3 at 6:45pm. If you’re interested in attending, hit our line!)

This Salome also differs from her predecessors because she’s not an adult soprano, but a little girl playing with a doll. Child Salome begets another Salome, who begets another Salome, until we are introduced to seven total Salomes: one for each of the veils with which she dances. Elza van den Heever plays the teenage Salome and sings the leading role. Her six younger selves act like a set of human Matryoshka dolls, representing the years of trauma she’s suffered at the hands of her pervy stepfather. Herod is so aroused by his stepdaughter’s dance (ew) that he offers to give her anything she wants. Instead of asking for a new Macbook or a Cartier watch (as I would if my dad handed me his credit card), she asks for the head of John the Baptist, who is conveniently imprisoned in the basement of the family’s haunted mansion for criticizing Herod’s marriage to his brother’s wife (Salome’s mom). Salome has been sneaking downstairs, where the Nevelson black interiors are swapped for a talcum white dungeon. “Jochanaan,” as he’s called in the opera, isn’t wearing the prophet’s signature camel hair garment, but a white loincloth. From where I was sitting, his body seemed to be caked in baby powder, and I swear the opera house smelled like a baby’s clean diaper. Salome throws herself at Jochanaan, begging for his kiss. He resists. She gets mad. He loses his head.

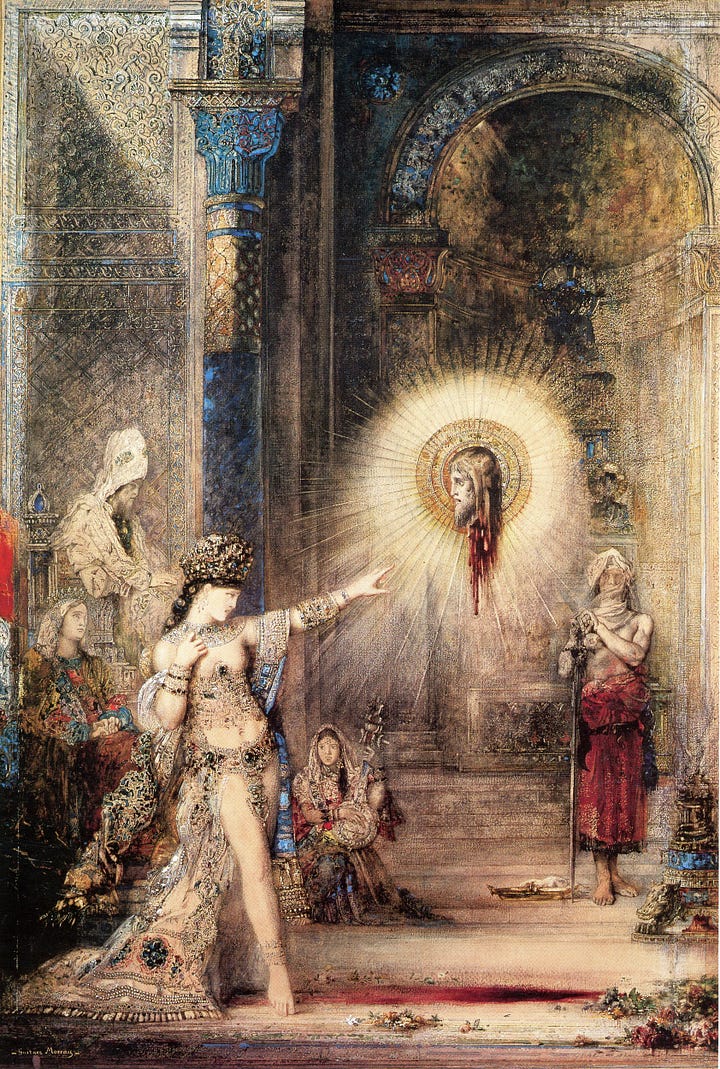

Watching this production of Salome while editing our podcast about The Substance in the midst of promoting One or Two felt like the universe was trying to tell me something. In One or Two, Frances Bethune’s fear of fatness leads her down a more treacherous path, where she must confront a younger version of herself and fight to be known as the “real” Frances. In The Substance, Demi Moore plays Elizabeth Sparkle, an aging actress who starts injecting herself with “the substance” to recapture her lost youth and fame. Elizabeth trades what could be a peaceful retirement for a one-week-on, one-week-off existence shared with Margaret Qualley’s Sue, Elizabeth’s younger alter ego who enjoys all that beauty and a perfect ass can offer her while Elizabeth rots away eating chicken and watching the Home Shopping Network. In Guth’s Salome, the titular character is a person fractured by conflicting desires and cycles of trauma. In Oscar Wilde’s time, Salome was a symbol of sexual depravity. The story goes that Wilde was inspired to write his play after seeing Gustave Moreau’s 1876 painting of the biblical princess dripping in jewels before John the Baptist’s bloody head.

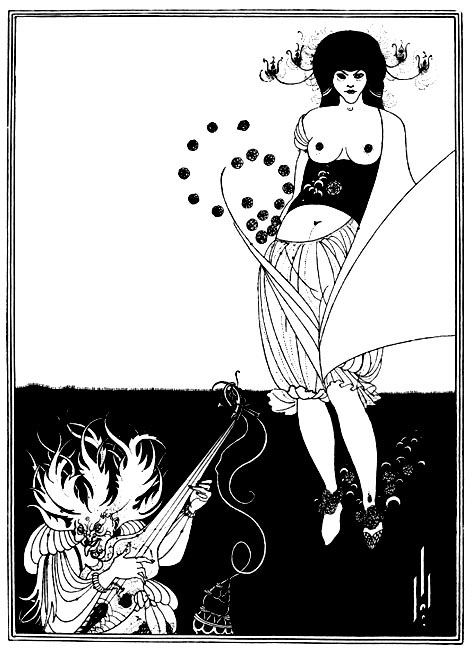

In Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for Wilde’s play, Salome is depicted in a similarly come-hither fashion: nothing covers her breasts and she dons a pair of sheer pantaloons. Despite her high neckline, van den Heever’s Salome is no prude—she cavorts with the best of them—but her pleasure is tinged with pain. Her younger selves look on while she gropes and molests Jochanaan. The older Salome hugs Jochanaan’s severed head while the younger Salomes clutch their dolls. Teenage Salome straddles Jochanaan’s lifeless body. Child Salome rides a rocking horse. This psychologically bruising portrayal of Salome feels like a major departure from Wilde and Strauss’s version, which sparked a phenomenon that the New York Times dubbed “Salomania” in 1908. The success and controversy of the play and opera inspired many famous women, including Maud Allan and Gertude Hoffmann, to perform their own versions of the Dance of the Seven Veils. From watching a bunch of clips on YouTube, I gather that the dance is often performed as a vaguely exotic, usually Orientalist strip tease. Veils are used to strategically conceal and reveal. I like Rita Hayworth’s 1953 version. Jessica Chastain’s 2011 rendition, performed for a horny Al Pacino, is hilarious. Nazimova’s 1922 interpretation is obviously epic. Relevant to the history of Salomania is belly dancing. In 1894, Beardsley named his illustration of the Dance of the Seven Veils, The Stomach Dance. The year before, at the World’s Columbia Exposition in Chicago, a group of belly dancers performed at the fair’s “Street in Cairo,” introducing the United States to a new art form and causing a major uproar.

Okay, back to the opera. Salome is not the only one with a split self in the show. I gleaned from the English subtitles that Jochanaan mostly sings about Christ. Jochanaan is locked up not only for criticizing Herod, but also because he is a harbinger of a new Christian era. Jochanaan couldn’t care less about how horny Salome is. He’s focused on his holy savior. While Salome’s lust is seen as opposing Jochanaan's religious devotion, her desire to consume the prophet’s body reminds me of the Eucharist. I’ve always found John the Baptist a puzzling figure, mostly because he looks a lot like Christ. If I learned anything from my art history classes, it’s that you can tell which one is Jesus and which one is John the Baptist because the latter is usually wearing some form of animal fur and holding a reed cross. But it’s easy to confuse the two. They were cousins after all. Yes, that’s right. The Virgin Mary was related to Elizabeth, John the Baptist’s mom. One of my favorite works at the Met (the real Met, not the other Met) is Master Heinrich of Constance’s The Visitation. This gilded, polychrome carved-walnut statue is from the very early fourteenth century and captures the moment when Mary and Elizabeth, both pregnant with their holy babies, got to hang out. The two women are eerily similar. They have the same golden curls, golden dresses, white veils, and even the same rock-crystal cabochon pregnant bellies. The figures were formed from the same piece of wood—their interlocking hands indicate their point of connection. Is that not reminding you a little bit of The Substance and One or Two?

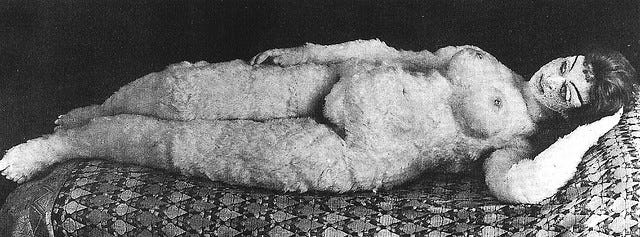

I have one last case of mistaken/severed identity to discuss before I conclude. Strauss completed the score for Salome in 1905. Early efforts to stage the opera in Europe were met with censorship. Conductor Gustav Mahler was desperate to bring the show to Vienna. Mahler was so passionate about Salome that he threatened to quit the Court Opera over it. Strauss warned him that his artistry was worth too much “to put anything at stake on Salome’s account.” I read in the Met’s program notes that when Mahler first saw Salome performed in Berlin, he wrote to his wife: “One of the greatest masterpieces of our time… It is the voice of the ‘earth-spirit’ speaking from the heart of a genius.” What the notes fail to mention is that Gustav was married to Alma Mahler, a Mandylion heroine of particular note because she was so hot and awesome that one of her boyfriends, Austrian artist Oscar Kokoschka, made a life-size doll of her after they broke up (they dated after Gustav’s death in 1911). Kokoschka hired a dollmaker to do the actual crafting of his Alma doll, but he was very involved in its design, sending letters with specific instructions: “Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump and the limbs.” Expectations exceeded reality. Kokoschka derided the dollmaker’s decision to coat Alma’s body in feathers—“The outer shell is a polar-bear pelt, suitable for a shaggy imitation bedside rug rather than the soft and pliable skin of a woman.” The feathers impeded his ability to dress up the doll.

In the end, like Salome before him, Kokoschka cut her head off.

Let’s just hope we can all keep our heads on this fine Tuesday.

X,

Mabel

Mabel, one of your best. Thank you for the Salome education.