If this is brat summer then tell me what is brattier than flying 3,000 miles to mope around your mom’s house in Los Angeles, drinking Erewhon water you didn’t pay for and complaining that the city has no history. Well, reader, that is exactly how I spent the first week of June. But I could only ignore the fact that LA’s storied history was all around me, in the architecture and landscape of the Hollywood Hills, for so long. After all, the city is a place where it never rains, where nothing goes to ruin even as everything is forgotten. So, ultimately, I decided to return my brat card to the (brat) pack and set off in search of some history.

I had already kind of forgotten about the symbolic power of the glamorous local past’s most iconic monument, the Hollywood sign. My mom and I walk the dogs past it en route to the Hollywood Reservoir every morning, its significance annihilated by overexposure. Erected in 1923, the sign originally served as an advertisement for the Hollywoodland real estate development. Its 50-foot tall white letters were covered in 4,000 lightbulbs which lit up in segments, “HOLLY,” “WOOD,” “LAND.” Searchlights in the foothills added to this spectacle. In 1932, a hiker found the body of actress Peg Entwhistle, who had jumped to her death from the sign’s H after finding out that a large part of her role in Thirteen Women had been cut from the film. In the 1940s and again in the 1970s, the sign fell into such disrepair due to “wind or vandals” that it needed to be replaced and preserved by the city. The latter campaign was led by Alice Cooper and the Y was furnished by Hugh Hefner at the cost of $27,778.

Other remnants of the Hollywoodland development pepper the neighborhood; the original gates stand at the entrance to the village, next to Aralda, a vintage store where I once saw Addison Rae having an amazing time trying on $7500 80’s Alaia couture, and the Beachwood Café, which is weirdly crowded because Harry Styles sings about it but makes up for it with their basil mint lemonade. This zone still has some of the cute craftsman houses that were part of the original development, furnished with bronze plaques that alert thieves and vandals that Hollywoodland security is on patrol. There was also a weird box that read “time switch.”

I was going to let the time switch remain a whimsical mystery but curiosity got the better of me so I did some research: it's literally a clock in a box, a timer that turned on the street lights in the early days of the twentieth century. It’s hard not to connect the box with Chris Burden’s “Urban Light” installation at LACMA, which is made up of decommissioned LA street lights that Burden collected at flea markets.

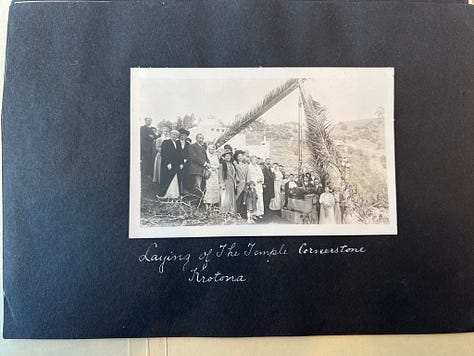

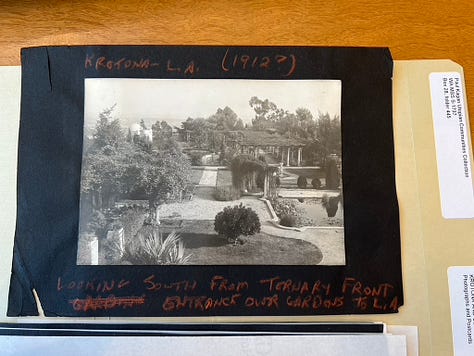

All of this is fine and grand but I craved OLDER STUFF so I continued down the hill until I came upon the remnants of the Krotona Colony, a Theosophist settlement that existed from 1912-1926, at which time it moved to Ojai where it remains to this day. I’ve been studying Krotona via the Paul Kagan archive at Beinecke and was excited to learn that a lot of the original buildings are still standing, and within walking distance of my mom’s house. Theosophy was founded by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891), worthy of her own newsletter but mostly irrelevant to the later Hollywood settlements, who attempted to create a spiritual doctrine that reconciled all world religions and sciences into one unified ideology. As this doctrine developed, and as the society founded branches in British Colonial India, karma and reincarnation as well as colonial hierarchical structures came to play an important role in the religion, giving it an orientalist attitude reflected in Krotona’s architecture.

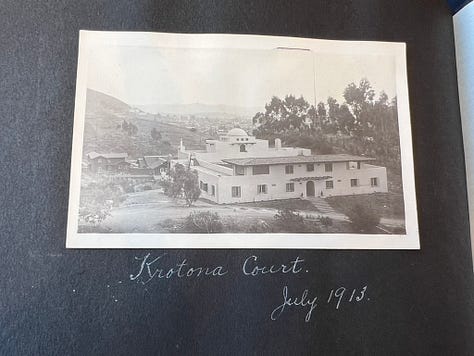

Krotona was intended to be a school, named for and “patterned after the institution conducted by the noted philosopher, Pithagoras [sic], of classic times.” Architects who worked on the colony included San Diego firm Mead & Requa, Arthur and Alfred Heineman (who designed the world’s first motel), Elmer C. Andrus and Harold Dunn. While at the time of their construction they were situated as far into the hills as Los Angeles extended, the remaining buildings now sit, converted into apartment complexes, at the lowest edge of one of the city’s most desirable neighborhoods. Even in the period between 1912 and 1926, the property value increased significantly, one reason for their move to Ojai.

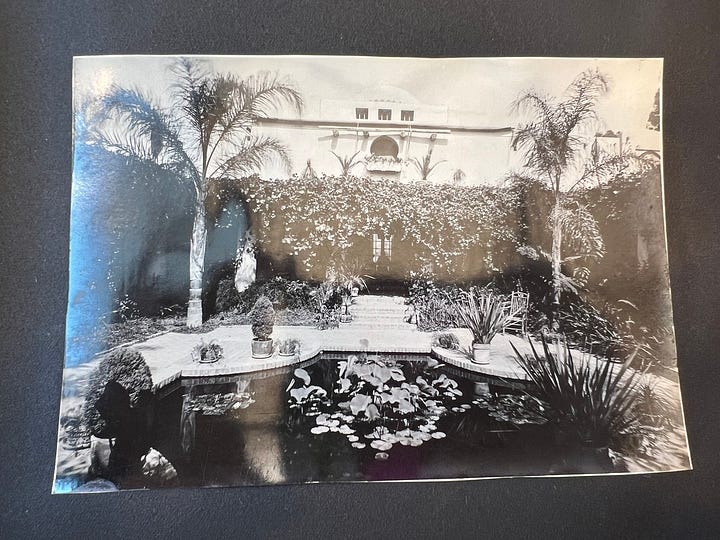

My mecca was the Krotona Inn (2130 Vista del Mar Avenue, completed 1913) which, as is the trend, has since been converted into apartments. The building, also called the Krotona Court, was designed by Requa and Mead, architects from San Diego known for their mission-style buildings. The Court was the Theosophical school’s central hub, made up of lecture halls and apartments. A vegetarian cafeteria opened onto the patio, featuring a pergola of thick columns supporting a eucalyptus log framework. The aptly named “Esoteric Room,” positioned on the east side of the building, was housed under a large dome. Alfred Willis, whose survey of the remaining Krotona buildings was my guide, argues that the dome, a singular Moorish feature in an otherwise austere design, “may have appealed especially to Theosophists since Moorish building in Spain could be understood as a synthesis of eastern and western cultures and hence represent the synthesis of eastern and western belief systems in modern Theosophy.” Theosophical doctrine, which promised to marry eastern religion and western science, was here made manifest in the building’s ornamental scheme. This is evident in other features of the Esoteric Room’s layout as well. Willis wrote:

Opposite the entrance, and raised on a brick dais, stood a built-in altar in the form of a locked cabinet. This cabinet was designed to contain, perhaps, certain sacred books or other spiritually charged articles believed to impart their ‘magnetism’ to the Esoteric Room’s domed space: thus the potency of the group meditation would have been enhanced. The altar directed all conscious attention strongly toward the east, the direction from which many Theosophists believed a World Teacher had recently emerged in an incarnation of the great soul of Alcyone, named Krishnamurti.

The building was carefully laid out around a reflecting pool in the central courtyard, surrounded by verdant landscaping “including the sacred lotus.” Well it is in keeping with Islamicate styles to utilize water in architectural space, the pool’s reflectivity also referenced the theories of Theosophy’s most prominent architect, Claude Bragdon (1866-1946). Bragdon believed that a coming evolution would allow people to project into the fourth dimension, conceived of as another spatial dimension. One of the ways he illustrated this concept was by using reflections as analogies for higher-dimensional space.

When I visited, I found the reflecting pool intact, along with the dome over the Esoteric Room. I also found one really nice woman who let me into the courtyard and tried to feed Fran turtle food while I took pictures. Unfortunately, a group of really mean women in sunglasses who worked for the “management company” told me that I was trespassing and couldn’t take pictures.

After I was rudely removed from the Krotona Inn, I walked by Moorcrest, a grand house designed by Theosophical society member Marie Russak Hotchener—a rare example of a female architect working in the period. The property was well known for having been rented first to Charlie Chaplin and later sold to parents of the actor Mary Astor, at the time engaged to John Barrymore. Hotchener maintained ties with the property, becoming Barrymore’s private astrologer. I could tell from the outside of the house that someone famous lives there simply by vibe, and I was right: it's now owned by Andy Samberg and Joanna Newsom.

As I really consider myself a scholar of failure, failed utopias are heaven to me; Krotona in particular represents an early experiment in the kind of hopeful New Age communal living, run through with something slightly sinister, that gives Los Angeles its unique appeal. Writing about this in his book on the subject, New World Utopias: A Photographic History of the Search for Community, (New York: Penguin, 1975), Paul Kagan has written:

This is the core of the California dream, the weakness in its strength. The habits come back, the emotional structure of man is not so easily changed, and what was experienced as freedom and “togetherness” soon becomes only a memory or an ideal. Disillusion sets in and is tranquilized with drugs, a succession of gurus, or with ideas, even great religious ideas and programs. We are back full circle: America leads to America.

That was it for my walking tour of Krotona, but it did not totally quench my thirst for Hollywood history. Among the Kagan papers I found a photograph, almost completely black, with lights strung like pearls through the center of the image. When I found this image, it slowly dawned on me that this was the view looking out over the city from the Hollywood Hills in 1912. In an attempt to occupy the ambience in which the photo was taken, I later had dinner at Yamashiro Gardens, a huge piece of property in the hills with beautiful gardens, sweeping views of the city, and mediocre Japanese fusion food. The main building housing the restaurant and bar was completed in 1914. It was supposedly a replica of a Japanese palace in Kyoto, but in reality it was a fiction, the fantasy of architect Franklin M. Small and the owners, Adolph and Eugene Bernheimer, “German-born cotton barons and avid Asian Art collectors," according to the restaurant’s website. Constructed from teak and cedar, decorated with gold lacquer and bronze dragons, the walls were hung with expensive silks and antique tapestries from the Bernheimer’s collection of Asian art. Yamashiro is a popular location for shooting movies set in Japan. The palace freely mixes elements of many Asian cultures, including China and Japan, creating a pan-Asian pastiche and orientalist fantasy that not only links it with the architecture of Krotona but also has served as the model and backdrop for Hollywood’s sometimes careless depictions of these cultures.

After one of the brothers died in 1924, Yamashiro and the collection of Asian art were sold off. Its new owner turned it briefly into a clubhouse for old Hollywood elites called the 400 club, but with the economic downturn of the great depression the club was shuttered. With the start of the second World War came a wave of violent anti-Japanese sentiment that was, somewhat erroneously, laid on Yamashiro–a construction of two Germans that never had anything to do with Japanese nationals. After locals came to believe that the main house was being used to broadcast information to the Japanese, the property was vandalized and eventually its Japonisme details were covered over as the building was converted into first a boys school and later an apartment complex. After the war, the building was sold to Thomas O. Glover, who intended to modernize the apartment complex. However, when construction started, revealing the original silk walls and cedar frame of the Bernheimer’s house, Glover decided to restore the house to its original glory. Thanks to Glover, I got to sit on the patio worrying that the Koi fish were oddly still, sipping a devastating pink mezcal drink.

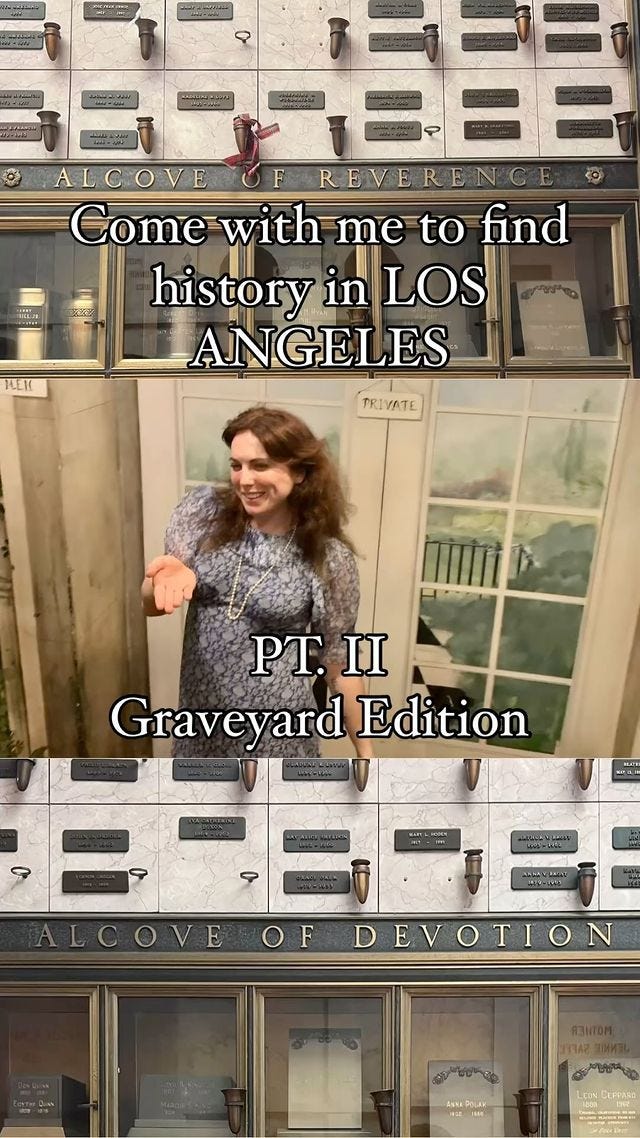

The final stop on my search for history took me straight to the source, dead people. I wanted to visit the Hollywood Forever Cemetery because of this video of Kenneth Anger // my erstwhile obsession with Anger’s 1959 book, Hollywood Babylon. I was not disappointed. After I told the security guard that I was there to “visit the cemetery” he said I could park literally anywhere I wanted as long as there weren’t cones. From anywhere I wanted, I walked around the small artificial pond, kissed Rudy Valentino’s grave, and saw the Grecian ruin that houses the remains of Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Sr. I saw the grave of the woman Alec Baldwin killed, which was pretty upsetting, and Hattie McDaniel, which was beautiful. Johnny Ramone had Rob Zombie and Vincent Gallo blurb his tombstone, something I hadn’t realized was possible. And best of all, I saw the small shrine to Eve Babitz in the Alcove of Adoration which contained a few of her books, some plastic heart-shaped earrings, and a vape.

Thus concludes the tour! I also went to the Museum of Jurassic Technology which I can’t recommend enough but don’t feel equipped to speak on and met my niece which was a highlight but can’t really be shared with you all. I adore you nonetheless! We’ve got big things cooking, can’t wait to talk soon :) XOXO

As always,

Madeline