MM #22: everything was ugly and nothing made sense

Madeline reviews Megalopolis in Substack’s truest form: the gift guide.

I was going to write a newsletter about mummies but then I watched Megalopolis and my thoughts drifted from Egypt to Rome. Because I’m a scholar of stuff—and because everyone else is doing it—I will be unpacking my thoughts in the format of a gift guide. As Mabel has previously stated, we have no idea how to make money from anything we do, it’s all pure love of the game.

For those of you who don’t know, I have an enduring obsession with “architecture.” I’m not talking about buildings and I could care less about practice. My fascination begins and ends with architecture as a cultural object, namely with the popular imagination’s bizarre notion of what an architect actually is. In this regard and no other, Megalopolis was a perfect film: Adam Driver’s performance was baffling, characters spoke exclusively in terms of utopian projects and sweeping social changes rather than addressing actual issues, money was no object, megalon was plants (?), everything was ugly and nothing made sense.

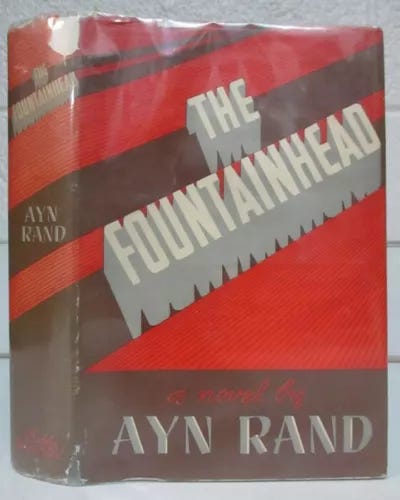

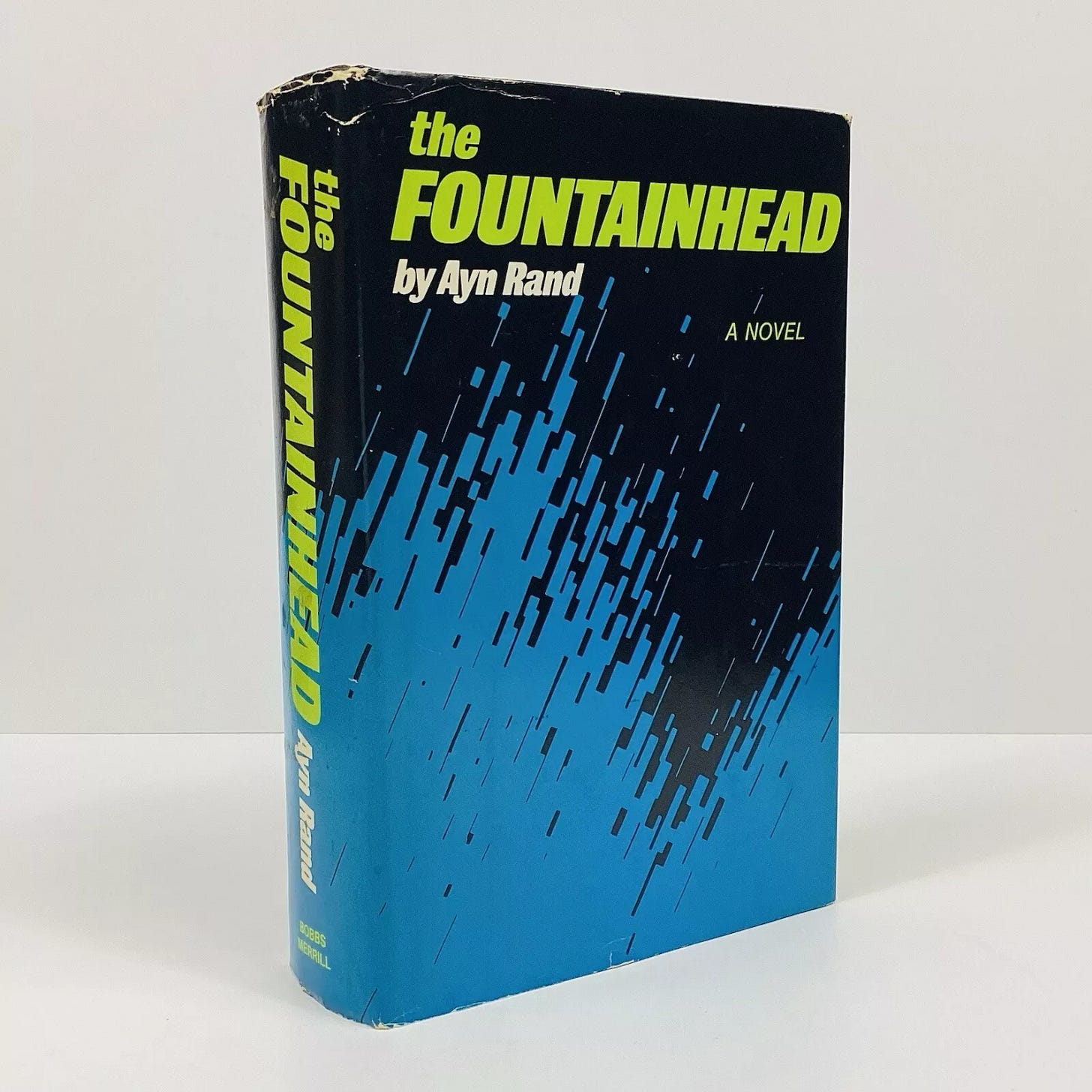

I blame my obsession with architects on the fact that when I was about 9 years old, my mom’s really pretty friend suggested I read Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (1943). I read it and now I’m pretty too. I’m not saying there’s a correlation, just stating a fact. The Fountainhead is a book about one guy who’s an uncompromising genius and a bunch of other people that are compromising not-geniuses. That’s a heady a cocktail for a kid already pre-disposed to delusions of grandeur.

I haven’t picked up the book since I hit double digits but I would be willing to revisit with a fully developed frontal cortex. Plus, there are some beautiful old editions out there:

Though I haven’t read the book since the Bush years (appropriately, I might add), I did see the 1949 film adaptation of The Fountainhead when it was playing at Metrograph a couple years ago.

In my favorite scene, a bank’s board slides a condom of neo-classical ornament over Howard Roarke’s model, a prophylactic against Roarke’s modernist impulses. Roarke’s character was loosely based on Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work is much more ornamental than people defining modernist aesthetics—like Henry Russell Hitchcock and Rand herself—are comfortable with. As a retributive craft activity, consider adding neoclassical facades to models of Wright’s works available here and here.

While Roarke’s intellectual gigantism dwarfs all men he meets, his love interest, Domique Francon, gives him a run for his money. Ayn Rand described the character as herself “in a bad mood,” a quip that is now my guiding principle for 2025. Why not buy the Dominique in your life a Cire Trudon candle in the shape of a bust so she can enjoy her two favorite things: beautiful art and watching shit burn.

Textual context makes the gift even more thoughtful: Cire Trudon’s website identifies the model for this one as Louise, herself the daughter of architect Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart (1739-1813) who designed the Stock Exchange building in Paris and transformed the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Rand’s worldview, which privileges independent genius over collectivity, was sticky—it remains the framework through which we view modern architecture, especially skyscrapers. When it opened in 1923, the Shelton Hotel, a proto-skyscraper—was the tallest building in New York City. It stood at a mere 387 ft tall. A clever stepped design allowed it to bypass height restrictions, a move emulated in the design of more iconic New York landmarks like the Chrysler Building (1929, 1046 ft tall) and the Empire State Building (1931, 1250 ft tall). These days, the Shelton’s legacy is mostly forgotten, it now appears measly in the midst of midtown’s “supertalls” which carry the torch for Rand’s brand of capitalist progressivism. However, in its day the Shelton housed some notable artists and architects, encouraging community and collectivity as an amenity of urban life. Note-worthies included Georgia O’Keefe, Alfred Stieglitz, and the architect on whom I wrote my master’s thesis, Claude Bragdon. Apparently, the three liked to breakfast together. In her notes for The Fountainhead, Rand calls out Bragdon’s “silly mysticism,” a jab she would surely have extended to his pals. Yet, its the mystical quality of the city that O’Keefe captured in her New York paintings, which included views of and from the Shelton as well as images of the Radiator Building on Bryant Park and the Brooklyn Bridge. In these works, architecture dissolves, buildings blend into one another, and light obliterates megaliths of steel and concrete. The city’s famous skyline gives way to both subject and surrounding—to the profound overwhelm of the sublime. These paintings were exhibited as a body of work for the first time this year at the Art Institute of Chicago, the show is closed but the accompanying catalogue is worth perusing.

Ironically then, it’s within these skyscrapers that we find alternative modernities—projects for living that propose a different future. One might argue that Manhattan, with its vital composition, fleshy color palette, and encroaching vegetal life, is proto-megalon—the biomorphic material constituting Adam Driver’s utopian project in Megalopolis. Driver’s designs were inspired by the work of artist Neri Oxman of the MIT Media Lab who I believe served as a consultant on the film. This was just another pearl on a string of bad judgements Oxman has made which include giving an Orb to a known sex offender and briefly dating Brad Pitt. Oxman herself seems smart and pretty. You can learn more about her design approach, which she calls ‘Material Ecology,’ in this book.

Thus far, I’ve been avoiding plot summary because the movie was downright belligerent. It was kind of like if The Fountainhead and Metropolis and Click (in which Adam Sandler’s character is also an architect!!!!) were combined but set in Ancient Rome in the year 2300 AD. Knowing much more about Click than I do the Roman Empire, I had very little to grasp on to. If someone wants to gift me the collected volumes of The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, I would love to learn.

Coppola married Roman history with another body to which I’m allergic: architect-designed furniture. That said, while watching the cringiest scene in the movie, my eye found respite on a Josef Hoffmann or at least Hoffmannesque chair. I can’t imagine a chicer addition to my apartment, complete with tiger print seats.

I will say, Aubrey Plaza was so good that she’s the only character whose name I remember. I was simply enamored of the coked out 80’s excess of Wow Platinum’s wedding. If I had $25,000-$50,000 lying around, I’d get a vintage Bulgari serpenti watch and make people call me Aunty Wow—the black and gold feels especially on the mark.

If Shia LeBouef’s look is more your speed, might I recommend some eyebrow bleach.

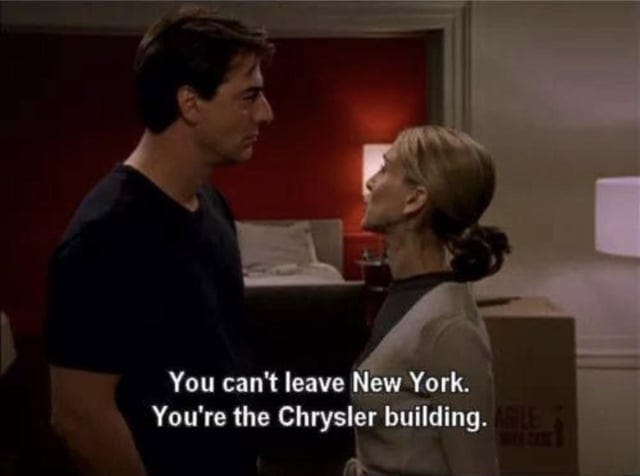

And if you’re shopping for someone with a personality disorder this holiday season, why not take Driver’s weird triumph over the Chrysler Building as inspiration? With this snow globe, your psychopath can hold all of New York in the palm of his hand.

After doing some homework, I found out that the top floors of the Chrysler building used to be occupied by a fancy club, The Cloud Club, which was known for its Dover sole and larger-than-regular-sized grapefruits. Either would make an excellent addition to a gift basket.

The club closed in the 70s but if you want to visit the crown of the Art Deco landmark today, I have good news and bad news. The good news: it is possible, but you may not like what happens when you get there. A New York Times article from 2005 describes the experience thus:

Even for a visit, it is fortresslike, and isolating—the standard king's complaint—to be this high. It is uncommonly quiet, momentously still, the air of irreversible decision. Being inside a chess piece, instead of having it in hand. You expect Orson Welles as Charles Kane, the shadows of clouds troubling his face, not Dr. Charles M. Weiss, a dentist who specializes in implant surgery.

According to Google, the space is still occupied by a dentist’s office. As I write, I’m giggling imagining Driver crawling out of the dentist’s window to dangle off the building. Incidentally, I went to the dentist in the Empire State Building when I was in high school, highly recommend. Book an appointment for a loved one as a holiday gift! There is a certain kind of mastery, unappealing to the likes of Driver perhaps, in absorbing New York’s most iconic buildings into the quotidian aspects of your life. You become New York in those moments.

Other ideas inspired by Megalopolis / the alphabet:

For your favorite tyrannical genius, consider an I-beam on which to contemplate (these ones are returnable for 30 days!!). Or perhaps your crazy might prefer Driver’s hottest accessory, a T-square of his very own.

May I also briefly suggest DIYing one of the “Design Authority” jumpsuits, which were undeniably cool, or buying a rather small carpet on which a loved one can place a baby?

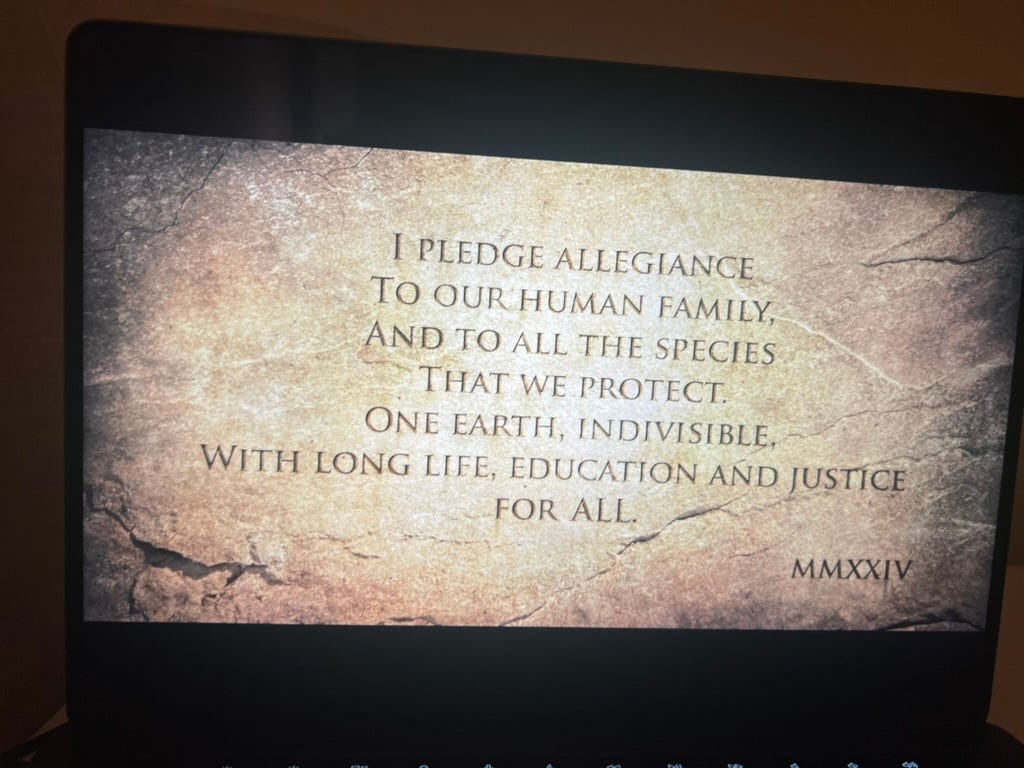

And finally, I leave you with the same thoughtful meditation that Coppola chose to end the movie:

JK, that makes me want to die!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! I’ll leave you instead with a reminder that the next episode of 1-800-1800 is available a week from today :) If you subscribe it just shows up!! In this one we tackle 1814 and if you ever wanted to hear me and Mabel guess what the British military history might have been like, boy are you in for a treat. Also, new books soon. More to come on that. TTFN!!

As ever,

Madeline

Not NY's tallest building, per wikipedia, the Shelton: "The building contains setbacks to comply with the 1916 Zoning Resolution; at the time of its construction, the Shelton was quoted as the world's tallest hotel."